01: Fun

4/5 '17

01: Fun

4/5 '17

I have always loved roller skating.

I struggle with how to explain this, fluidly. Everyone can tell the story of their first love or something they love, but really, the core of it, the gold inside the egg come down to two questions:

What freedom did it grant you?

Or conversely, "What safety did it provide?'

As an adult woman, I vacillate strongly between these two needs: the need to feel safe, the craving for freedom. Routine and schedules that span more than a few days or weeks give me a tight laced feeling in my chest. As children came into my life, the driving need to be alone along with the perishment of personal time (note: I am a solo parent of two) pushed up like an insistant animal at the backdoor of my thoughts.

I skated derby for two, short, intense years. They were also the two years I'd relocated cross country and started a new career. My derby career ended quietly and without fanfare - or anyone noticing really- when I booked an away job for three months. I took my skates, but I never went skating. It was a ghosting break up with skating, in a way, I just knew I couldn't but I couldn't really bear to explain to myself why. They were all compelling, professional reasons. My job relies on the health of my knees and feet. Solo parent. Sole provider. My career has physical requirements.

Derby had been an intense outlet. I could never put the time into skating that I longed to, but what I learned there was incredible. I could fly, or feel like I was flying. I never really attained any sort of strong skill set as a skater, or so I felt, but for me it had been worth it.

I was on another job, a few weeks ago. As I took out my kit to prepare for the job, my neglected skates rolled out of the closet, denting my Prada shoebox, as if saying, "What's the deal, Prada, can't take a hit?' I looked at them and rolled them gently back. I thought, to myself how my business partner and I often talk about our "fun check in's." Fun check in's go like this.

We do the activity (drinks, etc)

We head home.

We text each other, "That was fun!"

Until one night she said, "No it wasn't. I don't know what fun is but that same bar, those same drinks.. it's not fun anymore. I don't know what fun is but I am ready to find out again."

I laughed. But it was one of our side projects. One we'd joke about, "Have you had any fun lately?" and laugh, and say, sadly, "Nah, not really."

My skates looked like fun. I set them outside the closet and went to work.

That night on the shoot, I ran into someone I'd skated derby with. It felt like another lifetime ago, I hadn't even recognized this person out of context but they said the magical words...

"Want to go skating sometime?"

A week later, we were pulling up to a rink and ducking through the darkness to slip feet in skates. I pushed out on to the floor, and felt that same feeling that skating has always given me, since I was very young. Freedom. The music is loud, you don't need to talk, just move. This, I thought, this is fun.

I still have the same constraints, in many ways. I am still a solo parent of two children. My son is a high level athlete in a another sport. There are a lot of checks and balances. I don't know if I could commit to a derby team, if one would have me. But that night, I thought, there must be to be others ways to skate, to do this, other than just the rink. And there are. There are teams like the Moxi Skate Team.

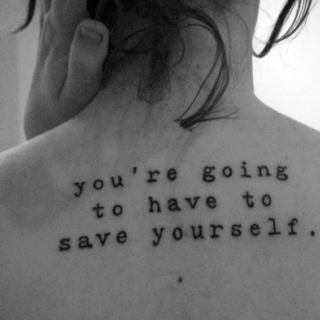

I'm not good with routines and schedules. Augusten Burroughs, in This Is How: Surviving What You Think You Can't writes about how many of us move in deeply entrenched habits, even when we travel. It's valuable to think about, if you aren't meeting the person you want to meet, if you don't have the friends that you think would fuel your heart and light you on fire with ideas, or, if like me, you have felt a lackluster wondering that whispers quietly, corrosively, "What if this is as good as it gets?" Because of course, that's a lie. It can always be better, or even sublime, if you are willing to be uncomfortable and move outside of routine. Just as it can always be much worse, for no apparent cause or reason at all. But it's up to you to craft it, no one is going to do it for you. No one will ever care about your happiness as much as you do, so it's yours to build. And if you struggle with that, well, there's always people a little bit ahead shouting out encouragment if you look in the right places.

I suppose....I suppose.... I've learned to listen to that little irrational impulsive voice inside me that can feel the electrical thrill of what is destined to come next. My own Tinkerbell lantern. I've learned to trust it as far as it can be trusted, which isn't very much, but more importantly, to listen to it as it is wise. So when I roll over, unable to sleep, restless, with a bruised and warm feeling in my chest, like a distanced lover, to watch yet another video, I think it's time to give in. Relent.

So. Regardless of the weight I feel right now, the plodding rhythem that we must sometimes adapt to to finish our projects (artistic or otherwise), my responsibilities and that I've lost touch with all my derby friends...

I ordered the Moxi Lolly Skates yesterday.

No idea when they arrive, but when they do, you'll know.

Yrs truly in the silvery light of the late afternoon-

QRC

PS Ended up watching Planet Roller Skate and practicing two wheel turns while on a call this afternoon. Put that under the hashtag fun, babes.

I really need to do the same. When you mentioned that people keep habits even when they're traveling? That's me. My job has me _constantly_ on the move, but I'm keeping some (really bad) habits on the road which lead to me not experiencing much in the way of new.

I started to break those habits, and it's lead to my being much more productive for illustration stuff.

But there's a lot more breaking to be done.

Anyway - thanks for being inspiring. :)

Augustin Burroughs said that if you even change one habit, one thing... it can have a huge ripple effect. It's Lent and so I've been thinking a lot about habits and assumptions. They go hand in hand. It's not just the habit, it's the assumption that it's what pleases you, tastes good, makes you happy. I remember once taking bite of chocolate cake and realizing it didn't taste like chocolate. It was sweet, it was brown and it looked right but there was no point to the calories as it was not really the taste I wanted. That's a good analogy for where I am artistically in my own life, so I've been taking apart a lot of things I assumed would cause pleasure, fill me up, or make me happy.

Turns out really expensive skates make me very happy and that I don't really care that I just gave up four things that I thought I "had to have" to afford them.

What are the habits you are breaking? How is it working? What's the hardest part?

They're amateurs.

With that in mind, I spent a lot of time trying to figure out how I could in a quick and efficient way, make any random hotel room 'homey'. In the end, the most efficient trick I found was through tech. Specifically, an Amazon Fire Stick and my web connected devices.

Since I live a fairly digital life, this made it easy for me to see any tv show / movie / video / audio that I could want to lay my hands on - with only the effort of plugging in a DVI connector, a power connector and then connecting the device to the hotel wifi.

I obviously can't do anything about furniture / lighting etc.

The problem, as I'm sure you've already guessed is that this lead to a LOT of binge watching of stuff that was entertaining, but not very fulfilling or productive.

So my first 'habit break' has been to force myself to NOT set up that Fire Stick at all. Or rather - not at some hotels. This causes me to stop to _think_ a bit more when I am trying to decide what I want to do next.

So far, the decision usually includes some form of digital creation (writing or drawing/painting mostly). Good for productivity, but I really need to get off my ass and be more... physical.

So ummm... sorry about the _War and Peace_ comment, but yeah - that's what habit I've started with. There are a lot more that need to be burned down.

I travel a great deal, but not as much as you (it sounds). There was one year I... and my oldest child, spent over half the year in hotels. It was exhausting, all that weird, beige furniture, that weird surfacing that keeps the coffee ring, how I tired completely of the styrofoam coffee cups wrapped in plastic and longed for things like my own mug.

Some people use candles... I've done that before but I'm mildly forgetful and I don't want to start a fire. For me it's a small bluetooth speaker, my own ceramic coffee cup (washed out in the sink and put on the side) and a wool blanket I keep in the car. I'd strip off the comforter and put the wool blanket on the bed. For scent I had a linen spray...lavender....and soap from home. We're minimalist packers (I can do a 10 day journey including formal events on one not-packed-to-the-gills carry on, and that includes the kids clothing too) but those things simply made it work for us.

I did learn so much living out of hotels about efficient furniture and how little I really needed to feel "at home" anywhere. After those long years of work in and out of hotels (right after I ended my derby career) I bought a house and moved in. For two years most of the things I owned sat in the garage until I just... got rid of them.

Hotel gyms in my experience often barely work and pools can be questionable. I mostly found parks to run in, and now (of course) I'd skate.

What are your preferred forms of exercise? Does it relate to your creativity at all what you do physically?

I used to follow roller derby, I'm acquainted with a few veterans.

While that was going on for them, partner dance (salsa, etc.) was starting to happen for me and I think occupies a similar place in my life.

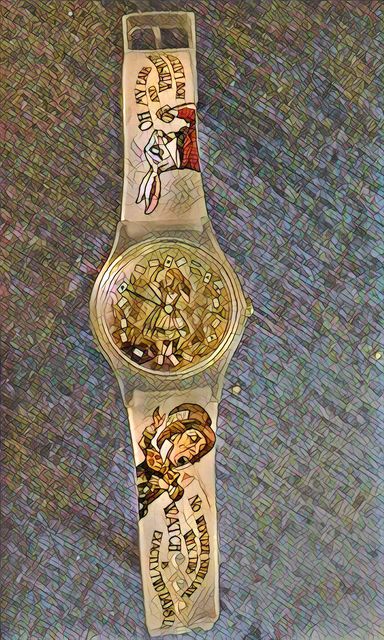

But I still wish someone would teach me to skate backwards.

For skating backwards, check out this video. This skater, also, is a huge personal inspiration to me for her outlook, her words, and her attitude towards learning new things. This is @GypsetCity as filmed by @indyjammajones

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6aAUZk1B7w0

If I had to choose between my therapist and blues dancing I would choose blues dancing in a heartbeat.

I like that you have a directory. I'm building a little list of my local skate rinks and their adult open skates. Not that I wouldn't do the family skate sessions for fun, but I worry if I'm trying new things that I'd wipe out a kid.

Actually, they have a website so bad it's wonderful. I get the impression you're nowhere near Philly, but just for the lulz:

http://www.palacerollerskatingcenter.com/Schedule.html